In a recent article, Vercel claimed that they reduced the number of tools they provided to their text-to-SQL agent by 80% just by allowing it to access filesystem tools such as cat , ls or grep .

Their main takeaway was: filesystems already solve most of the problems we try to address with complex tooling, so we shouldn't fight gravity, and we should let the LLM access environments where it can bash its way through the answer.

We also experimented with filesystems at LlamaIndex, going in two directions: sandboxing (using AgentFS as a base file system for Claude Code and Codex, as explained in this article) and exploration (an agent that can freely navigate files to find relevant information, available in this GitHub repository).

While sandboxing is a largely approved practice, file system exploration prompted some questions: how can “simple file search” perform as well as RAG? And, if it does, can it really be a RAG killer?

We decided to address these questions by carrying out an experiment, putting our fs-explorer agent to the test against a traditional Retrieval Augmented Generation system.

Find the code for this article here

1. Experimental Setup

Benchmark Dataset

We collected five recent arXiv papers on different AI/ML topics, and curated an evaluation set of five question-answer pairs (one for each of the files) asking for detailed and precise information about specific passages of the papers themselves.

Each task looked like this:

html

{

"question": "What limitations and future work perspectives are outlined for Recursive Language Models?",

"answer": "Limitations and future work for RLMs include exploring asynchronous or sandboxed sub-calls to reduce inference cost, deeper recursion beyond a single sub-call, and training models specifically as RLMs to improve reasoning and context efficiency.",

"file": "recursive_language_models.pdf"

}

You can find all the tasks here.

Traditional RAG

For the traditional RAG application, we decided to adopt the hybrid search approach, i.e. combining sparse (keyword-oriented) and dense (semantics-oriented) search and extracting the results with Reciprocal Ranking Fusion (RRF).

We used the following stack to create what we called a “rag-starterkit”:

- LlamaParse for advanced, OCR-driven text parsing and extraction

- Chonkie for sentence-based chunking

- OpenAI for dense embeddings and FastEmbed for sparse embeddings

- Qdrant for vector storage and search

The pipeline for data ingestion followed the standard flow: unstructured file to text, text to sentence chunks, chunks to dense and sparse embeddings, and then embeddings uploaded to a vector search engine, along with metadata (text content and origin file path).

Unlike the standard flow, tho, we decided to pre-parse the PDF files in our dataset and to make them available to the downstream processing steps through a disk-based persistent cache. In that way, the actual data processing could’ve been much faster and fault-tolerant: if something was to break during the chunking, embedding or uploading phase, the parsed text from the PDF files would’ve still been available, ready to start over.

For information retrieval, the flow follows the hybrid approach with RRF reranking we touched upon above:

- A query is received

- Based on the available files (our datasets), an LLM decides which one is most likely to contain the answer to the query, and we use that for metadata filtering

- OpenAI and FastEmbed produce a dense and sparse embedding representation of the query, which in turn are used to search among the vectors stored in Qdrant

- The vector search results are reranked leveraging RRF, and the top-n (

n = 1in our experimental setting) are used as context - An LLM produces a context-aware answer to the original query based on the retrieved context

Agentic File Search with Filesystem Tools

As said in the introduction, we already built an agent, called fs-explorer, to explore the filesystem and retrieve information on our behalf.

The agent, based on Google Gemini 3 Flash, has access to the following tools:

-

read_fileandgrep_file_content: used to read and perform regex-based search on plain-text files (.md, .txt…) -

describe_dir_contentandglob_paths: used to discover the content of a directory through a natural language description or using glob expressions. -

parse_file: Parse the content of an unstructured file (.pdf, .pptx, .docx…) into text using LlamaParse, or load it from cache if it has already been parsed.

The agent is built around a looping LlamaIndex Agent Workflow, and can call tool in a loop, as well as decide to stop once it reached the point at which it can reply to the user’s query.

Besides tools, the agent can also ask human for clarification questions, but we instructed the agent not to use human-in-the-loop during the experiment, as we wanted the tasks to be carried out autonomously.

In the experimental setting, as we said above, all the PDF files the agent had access to had already been parsed, so their full-text contents were available for faster access through cache.

2. Evaluation

The evaluation framework we built was centered around three key metrics: speed, correctness and relevance.

For speed, we simply recorded the start and end time of each task, whereas for correctness and relevance we relied on an LLM-as-a-Judge, prompting it to provide a 0 to 10 grade for each field comparing the RAG- or agent- produced answer with the ground truth.

Other details were collected too, although we didn’t use them in downstream processing:

- Final answers for both the agent and the RAG pipeline

- Tool calls made by fs-explorer before producing an answer

- FIle paths accessed by fs-explorer and used by the RAG pipeline as filter

- Errors

All the results are available in this file.

Once we ran the agent and the RAG pipeline through all five tasks, we calculated the average time taken, correctness and relevance.

3. Results

Speed

In terms of time performance, RAG proved to be faster than agentic file search, producing answers, on average, 3.81s seconds faster (7.36s VS 11.17s average time taken).

This is most probably due to the fact that agentic file search requires constant interaction with the LLM, which introduces more latency, whereas our RAG pipeline always uses four network calls (LLM to determine file filter, embedding, vector search and LLM to produce final response), all relatively fast.

Correctness and Relevance

For both correctness and relevance, the file-system agent outperformed traditional RAG, scoring 2 points higher on the average correctness (8.4 VS 6.4) and 1.6 higher on the average relevance (9.6 VS 8).

The most likely interpretation for this is that RAG is bound to context loss due to chunking and sub-optimal retrieval calls, so the LLM that generates the final answer has access to limited, sometimes incorrect context, and is more prone to hallucinations. On the other side, the fs-explorer had access to the whole file content: since our dataset files were not particularly long (22-52 pages), they could easily fit into Gemini 3 Flash’s context window (1M tokens), which made it easy for the LLM to have a bigger picture and produce more correct and relevant answers. This advantage would probably disappear if the files that are provided to the model get bigger, as they might overflow its context window and make the LLM output suboptimal responses.

4. Scaling

We decided to scale our experiment, first to 100 and then to 1000 abstracts scraped from the latest AI-related papers on arXiv.

In order to make the scaling less resource-intensive, we decided to apply the following adjustments to the experimental settings:

- General: we decided to use text-based abstracts to bypass the parsing phase. We cached the texts following the same schema detailed above, and injected them from cache within the data loading pipeline.

- Traditional RAG: we switched from hybrid (dense + sparse search) to sparse search only, using BM25 to generate the embeddings

- fs-explorer: we directed the fs-explorer agent to first check the metadata of the papers (reading the

metadata.jsonlfile that we created when downloading from arXiv), to help it with choosing the right paper based on the title instead of making it loop through all the stored files.

For both the 100 and 1000 evaluation cases, we used a set of 5 questions, each related to a different file (as in the previous experimental setting).

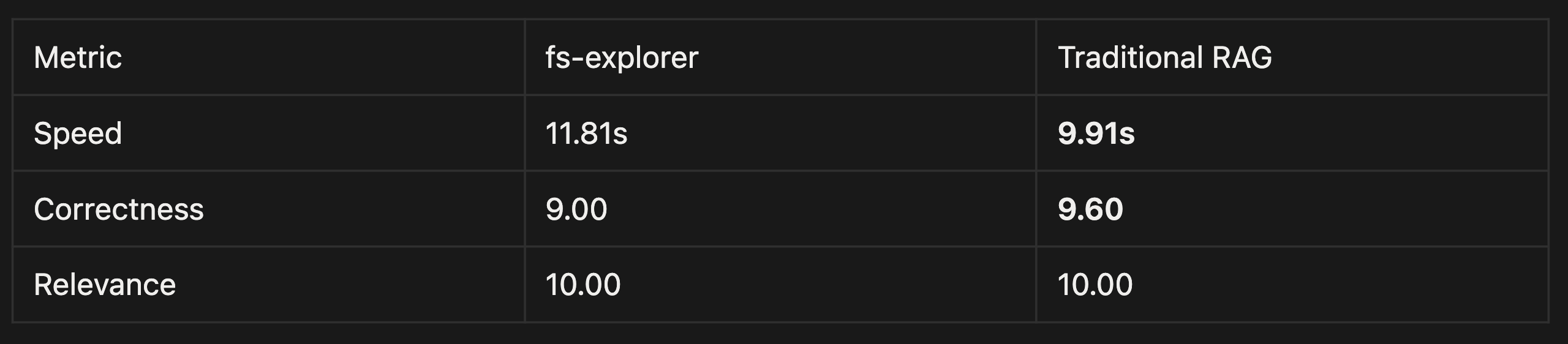

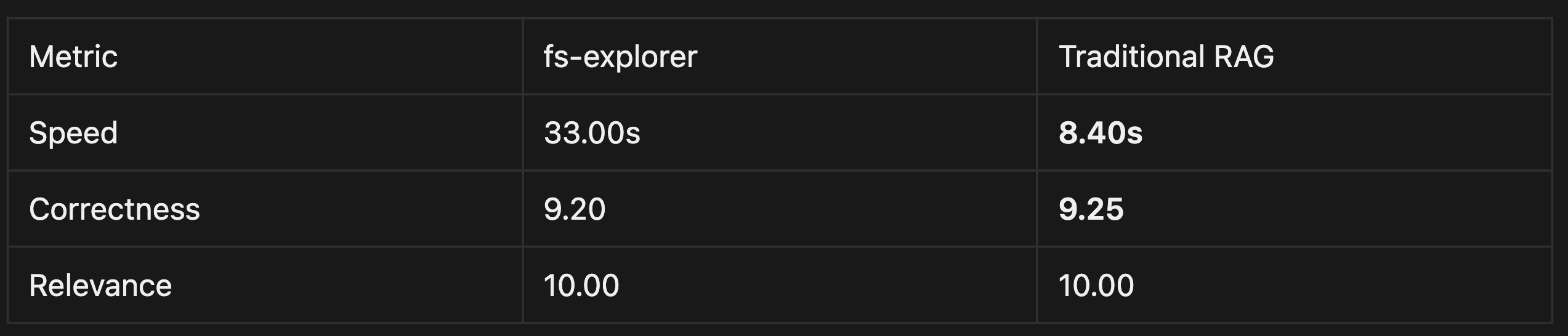

Contrary to what observed in the main experiment, scaling is easier with RAG than with agentic file search: as a matter of facts, RAG outperformed the fs-explorer approach in terms of speed (substantially) and of correctness (slightly), while performing at the same level for what concerns relevance.

Here are the summary tables:

Table 1: results for scaling to 100 papers

Table 2: results for scaling to 1000 papers

It is important to notice from the results that both frameworks performed very well (in absolute terms) for correctness and relevance, meaning that both traditional RAG and agentic file search can be a valuable solution for those who seek high-quality results. The only discriminant variable in the choice between the two approaches might be latency: agentic file search, having higher latency at a larger scale, might be more suited for background tasks and asynchronous processing pipelines, whereas RAG might be better for real-time applications where speed matters.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, what is the answer to the starting question: does agentic file search kill vector search? As for many other questions in computer science, the answer is: “it depends”.

Agentic file search with filesystem tools relies on a simple and powerful abstraction - filesystems - that is easy to understand and interact with for LLMs, but can quickly become a double-edged sword when the complexity and dimension of the files accessed by the LLM starts to grow and fills up the context window.

Also, moving around the filesystem takes time, probably more than what a RAG pipelines per-se would take. Still, agentic file search is definitely effective in terms of outputs, since it can rely on so much more context and information retrieval power than a RAG application: combined with the correct context engineering techniques such as context compaction, giving your agent access to file system can certainly yield high success rates.

RAG, on the other hand, sits on more complex concepts and algorithms grounded in advanced mathematics: embeddings, vector search, cosine similarity. This means every part of RAG, from file parsing to vectors, can and should be optimized (always resulting in slower time-to-value than a filesystem-based agent), and can and most probably will produce suboptimal results and will need some more adjustment and troubleshooting. Still, once an optimal and optimized setup is achieved, RAG can be fast, deliver high-quality results and tackle much greater complexity than filesystem-based agents, scaling to millions of documents and billions of embeddings.

In the end, everything boils down to the complexity of what we want to build and to the functional and non-functional requirements our system has: once we know that, we can decide whether or not agentic file search will be our vector search killer, or if we will continue with the good old RAG.